|

Shortly after composer Joe Waters arrived at San Diego State University, he articulated his mission:

“My goal is to blow the doors off the academy of music, and to let in all the music of the world,” said Waters in early 2002.

Now in his seventh year as Professor of Music and Director of Electro-Acoustic and Media Composition at San Diego State, Waters hasn't exactly knocked the doors down. But he is broadening the school's focus beyond the European classical music tradition that has dominated music education for centuries.

Waters, whose quartet, SWARMIUS, makes its local debut Saturday at the Neurosciences Institute, has the audacious notion that serious music – and music schools – should be inclusive of contemporary culture.

“It's an idea whose time has come,” Waters said. “So much of our culture now is a mixture of huge parts of Africa, as well as Europe. I mean, for jazz, rock, pop, it's been this enormously potent amalgam.

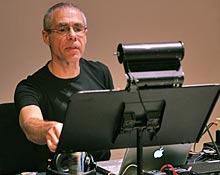

Composer Joseph Waters, violinist Felix Olschofka, saxophonist Todd Rewoldt, and guest percussionist Joel Bluestone

When: 8 p.m. Saturday

Where: The NeuroSciences Institute Auditorium, 10640 John Jay Hopkins Drive, La Jolla

Tickets: $20; $10, students

Phone: (619) 303-1509

Online: swarmius.com

“But in the classical music world, whenever there's a beat, it's still considered a little suspicious. You can't have a drum, and you can't have a drummer playing with a symphony orchestra. Immediately, it's like: That's got to be pop music. It's not serious.”

There's a beat to Waters' music. In a piece like “Intelligent Designs” (on the self-titled SWARMIUS CD), you could dance to it.

“I'm not the first person to combine Europe and African music,” Waters said. “That's been happening in classical music for a 100 years. There's a whole string of people, Gershwin, and even before.

“But it's still a problem that we wrestle with. And in terms of dealing with contemporary concerns, that's something I think we need to do to move the music forward.”

Waters' interest in other genres of music comes naturally. Now 55, he considers himself among the “first generation” of musicians who came to classical music through rock.

“That was the entry gate, and inside you discovered this whole legacy of classical music, this wonderful legacy,” Waters said. “But the way of getting there wasn't by taking violin lessons at the age of 5; it was by hanging out with my homies in the basement and banging on keyboards and drums and playing 'In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida.' ”

josephwaters.com (includes sound samples and downloads of Waters' music)

music.sdsu.edu/main-1/joew.html (Waters' page on the SDSU School of Music's Web site)

music.sdsu.edu/main-1/electrodiv.html (description of the new Electro-Acoustic Composition major at SDSU)

nweamo.org (home base of the New West Electro-Acoustic Music Organization)

swarmius.com (Web site for SWARMIUS; for more sound samples, check out SWARMIUS on myspace: myspace.com/swarmius)

“Many of my (peers) had actually played rock, but they they had been taught at some point that they were to leave that now and study the 'great music.' The difference is, I didn't believe my teachers. I did for a while; I tried really hard to listen to Arnold Schoenberg.”

Schoenberg's music earned his respect, but not his affection. Waters even tried playing Schoenberg over and over for his youngest son, figuring that the toddler might be a blank slate on which to imprint the eminent German composer's thorny, dissonant music.

It turned out, not only the kid, but the entire household hated Schoenberg.

“Every time I put it on, the house would break into chaos,” Waters said. “Everyone would be screaming at each other.”

Exactly why Schoenberg's music didn't work for him, or why it seems to be despised by a majority of the listening public, is a question Waters has spent considerable time pondering.

“The answer is, or at least part of answer is, for various reasons we don't get it,” Waters said. “It transcends our ability. It's about pattern recognition. You can't listen to it and understand it in some way that's not analytical.

“And people aren't analytically listening to what's going on. Music has to serve a function that helps them increase their ability to appreciate and enjoy in some way the moment-to-moment passing of their lives. They are not going to go for a piece of music that's like reading a technical journal.”

But increasingly, in Waters' estimation, it's not just Schoenberg, Webern and their modernist peers who are incomprehensible – Bach, Mozart and Beethoven make less and less sense to a younger audience.

“For these kids who are growing up on a diet of hip-hop music, they don't get the music of Mozart and Beethoven, even though hip-hop is built on it,” Waters said. “I mean, Mozart is somewhere underneath Eminem, he's lying there, but they just can't make a connection to it. To them, all that music is, it's categorically, cognitively (unavailable). It's this old stuff, and they don't get further than that.”

Waters is intent on closing the gap between Mozart and Eminem. While in Oregon (where he taught at Lewis & Clark College), he founded the NWEAMO (New West Electro-Acoustic Music Organization), which is devoted to forging “connections between the composers, performers and lovers of avant-garde classical music and the DJs, MCs, guitar-gods, troubadours and gourmets of experimental popular music.”

Since Waters' move to San Diego, NWEAMO has broadened its reach and now presents an annual festival in about a half-dozen cities worldwide, including San Diego (this year in October at SDSU), and has hopes of presenting concerts on the online virtual world Second Life (where the organization's board of directors already holds its meetings).

At San Diego State, Waters collaborated with like-minded faculty members Todd Rewoldt and violinist Felix Olschofka (and “guest percussionist” Joel Bluestone) to form SWARMIUS, which is dedicated to Waters' most potent weapon: his genre-defying music.

And Waters has started a new major at SDSU in Electro Acoustic Composition, intended for composers who, in the words on the university's Web site, began “their creative experiments within so-called 'Popular' genres such as rock, metal, hip-hop, electronica.” The program calls itself “one of the most forward looking in the world.”

Waters believes there is an increasing number of faculty at SDSU who are open to fresh ideas. “There is a group of us now who feel that the underlying principles of what constitutes an academy of music really need to be rethought, so that they in some way address who we are becoming as a culture,” he said.

| ||||||||